It was the second week of March, and we had just returned from an IMAGE team meeting in Toulouse, fired up and excited about the co-creation workshop we had planned with careers advisors and students at Hogeschool Fontys in Eindhoven. Emails were flying back and forth—and then the first major COVID outbreak in the Netherlands was announced.

In Brabant, where Eindhoven is located.

And so I asked my colleague: “My understanding is that Brabanters are being encouraged to stay in Brabant (the advice from the university this morning was – if you live in Brabant, don’t come to work here until given further notice) and we are being told not to come to you due to the Coronavirus epidemic. What is the advice on your campus?”

That day the advice to avoid in-person was optional, he said… but within 48 hours, the lockdown was mandatory, and both campuses and public transport were effectively shut down.

What to do?

We had the session scheduled and everyone was keen to continue, so we cast around looking for a way to run it online. Zoom? Microsoft Teams? One participant even suggested the gamer server Discord.

Try 1: Microsoft Teams

We settled on Teams because it seemed to offer the easiest way to share images and files, and to develop a shared document. As it turned out, though, it was not easy for everyone to access, and it was tremendously difficult to do an activity-based session as we planned.

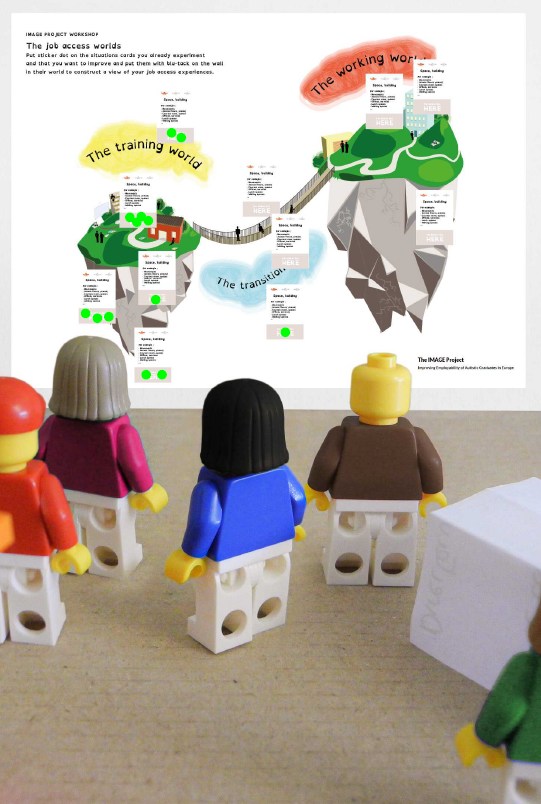

What had been intended was a series of group and pair activities; what actually transpired was more like a traditional focus group, where questions were posed and answered. We were able to use the Wiki feature on Teams to share images and activity descriptions to spark verbal interaction, but we know from past experience that physical actions in a workshop space—moving into groups or pairs; role-pay activities; using cards or other items to structure interactions; using pens, Post-It notes or stickers to share and rate ideas—creates more participation than what we experienced online.

That doesn’t mean that we did not collect the views and ideas we had hoped to gain, but the conversation was less fluid, less equal. Careers advisors spoke much more often than the students and recent graduate who were present, for example.

Try 2: Zoom

With that workshop under our belts, we sought to run at least one more (the original plan had been for three to four workshops, covering the geographical area of the Netherlands). This time, using online tools had a definite advantage in that we could include people from both Amsterdam and Rotterdam in the same group. We now had access to Zoom and understood a bit more about how to handle the much-reported security issues with this software, so we decided to give that a try.

Fortunately, we had fewer technical issues, as Zoom can be used relatively easily on the Web, e.g. without a special app or a Microsoft account. The sound quality was also reasonably robust, and it has a built-in recording tool that was easy to find. But as new users, we didn’t have a lot of knowledge of the tools that are possible within Zoom. We did do short breakout sessions, but there is actually much more that can be done, such as time-limited pair sessions.

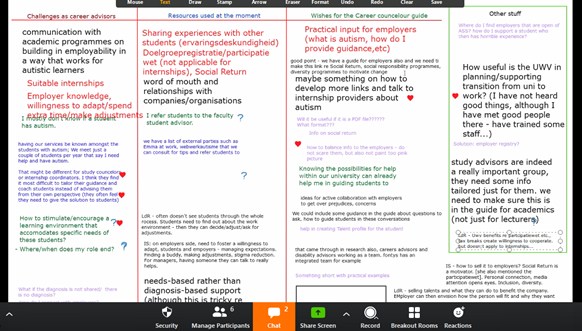

One Zoom feature that was useful was the ability to create an interactive whiteboard document. For us, this was a simple table where we could enter key issues, needs or points, using a different colour for each participant. This helped to ensure that the documentation reflected the actual views of participants, not a notetaker’s abridged version. However, not everyone found this feature easy to engage with.

Take-away messages

What can we take away from our experience of running co-creation workshops online?

First, it can be done – but the flat nature of online communication does detract somewhat from interactive co-creation formats. You may need to be more structured and directive than you had planned to be. Advantages, however, include eliminating some of the time and distance barriers that can make organising workshops difficult.

Disadvantages include time-wasting technical glitches that affect audio and video, and the difficulty of quickly building a sense of connection and shared purpose. We used an activity called ‘The Five Why’s’ for this, because it could be done verbally with everyone taking a turn. But even turn-taking can be tricky online, as we aren’t seated around a table or in a circle. We also couldn’t easily gauge whether participants were zoning out, bored or confused. That means we needed to build in checks every now and then – Is this making sense? Does anyone have a different view?

We also advise finding out how participants will access the meeting before planning activities, if possible. We had several participants who were accessing Teams or Zoom via a mobile phone, and on that kind of tiny screen, things like an interactive whiteboard are really tricky.

As long as the Coronavirus remains a life-threatening issue on and off campus, online meetings and collaborations seem to be here to stay. Experience of working on other projects, along with our experience of these two meetings, indicates that having shared documents or a whiteboard as the focus of the meeting really helps. It encourages everyone to have a say, offers a visual representation of presentation that can spark reminders to less active participants, and documents the ideas you have shared.

Whenever possible, schedule time to try out collaborative features built into your system of choice—you may not be able to do things just as you had planned, but perhaps there is a tool available that can help you reach the same goal in a different way.